I don’t normally comment directly on articles by others but an article by Matt Barrie with Craig Tindale called “Australia’s economy is built on shaky foundations, and it’s about to collapse,” has been sent to me several times for comment so I thought I would make an exception this time.

The gist of the article seems to be that growth in the Australian economy has been built on “a property bubble inflating on top of a mining bubble, built on top of a commodities bubble, driven by a Chinese bubble” and that “Australia has relied on China for too long – our whole economy is built on China buying our stuff. And it’s about to collapse.”

This note takes a look at this risk.

Crash calls for the Australian economy are like a broken record

The first thing to note is that there is nothing really new in the latest call for a collapse in the Australian economy. In fact, for as long as I have been an economist there have been calls for the Australian economy to collapse. Back in 1985, I recall going to presentations on fears the economy might soon “default” and require a rescue by the IMF. The crash calls have accentuated post the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). The Australian economy was supposed to have crashed when the mining investment boom ended in 2012-13 and every year since then there has been an ad on the internet titled “Australian recession 2014: why it’s coming, what to do and how you can profit” but the year just keeps getting updated to the current year. I guess it will be right one day.

Is China about to collapse?

China is Australia’s number one trading partner so Australia is more vulnerable to the Chinese economy than in the past. But warnings of a Chinese collapse have been around for years now and I continue to regard it as unlikely. The most common concerns about high and rising debt in China miss the reality that China’s high debt growth reflects its high saving rate (of around 46% of GDP compared to around 22% in Australia), which in turn gets largely channelled through the banking system as its capital markets remain underdeveloped. China does not rely on foreign capital (in fact it supplies savings to the rest of the world) and to slow its debt growth, it actually needs to save less and spend more (so very different to countries that normally have debt problems!) and broaden its capital market beyond the banks. But this will take time and the Chinese authorities will not act precipitously. And in the meantime, yes, there is a risk that some corporate loans will go bad but don’t forget much of the growth in debt has gone from state-owned banks to state-owned businesses and will be supported by the Government if there is too much trouble (just like the Chinese Government solved its local government debt problem of a few years ago).

But isn’t China at peak commodity demand?

Similarly, concerns about China’s property market and commodity demand are misplaced. The Chinese property cycle has regular ups and down as the property market is generally undersupplied but the Government periodically tries to keep a lid on prices. But every time there is a downturn in the property cycle (usually after Government moves to cool it down), out comes new crash stories. The “ghost cities” stories of a few years ago were evident of this but were literally just scary stories – they are part of an effort to decentralise away from crowded cities and the biggest “ghost city” (Ordos Kangbashi) is now almost full. The reality is that much of China continues to have a housing shortage as the population urbanises and many of the apartments built 20 years ago are now substandard and need to be replaced. So demand for steel and concrete from the property market is likely to remain strong for many years to come. Similarly, much of China remains under developed in terms of infrastructure. So yes, China is trying to wind back excess capacity in some sectors that have got ahead of themselves but peak raw material demand from China is a long way off. Yes, Chinese growth could slow towards 6% over the next few years but I doubt a hard landing any time soon. Certainly there was no sign of any hard landing in China when I visited it again in the last week – things were just as frantic as ever!

Australia has always had some export dependence

It’s worth noting that over the years Australia has always seemed to have some dependence on some foreign country in terms of export demand – the UK, Japan, it’s now China but as China’s industrialisation phase slows I suspect other countries will just jump into the commodity demand space (Vietnam, India, Pakistan) and in any case our relationship with China is also shifting across to services.

But the mining boom has long ended so why hasn’t the Australian economy collapsed already?

If Australia is so dependent on the commodity price boom and mining investment boom, why didn’t it crash when they crashed after 2011 and 2012-13 respectively? The simple answer is that the Australian economy is actually less dependent on mining and hence China than many commentators claim. In reality, mining activity is only 7% of Australian economic activity (or GDP) and agriculture is 3%, which taken together hardly suggests an excessive reliance on exports and China.

The mining boom basically meant that south east Australia – and sectors like manufacturing, tourism and higher education along with housing – was suppressed by high interest rates and the high Australian dollar. Once the commodity and mining investment booms went away and interest rates and the $A fell, south east Australia was able to bounce back offsetting the slump in Western Australia and the Northern Territory and parts of Queensland. So Victoria, NSW and even Tasmania were able to go from near recessionary conditions and at the bottom of state rankings a decade ago to now being at the top.

More than housing

This has not just been driven by housing-related activity, smashed avocados and flat whites (how come Chai tea brewed with soy never gets a look in?) but also in services like tourism and higher education (our third biggest export earner), which are booming. Even manufacturing is looking better. In fact, for many Australians the China driven mining boom was more a curse than a blessing – the saying in Sydney was that the people of western Sydney were paying the price for the mining boom in Western Australia.

Housing construction is starting to slow causing many to wheel out the disaster scenarios again. But the contribution to economic growth from growth in housing construction is regularly exaggerated. Last year it contributed around 0.3% directly to growth and indirect effects are likely to have taken that contribution to around 0.6%. In other words its relatively modest and a housing construction slowdown should be easily offset as the drag on growth (of around 1-1.5% per annum) from slumping mining investment is nearly over, infrastructure spending is booming (partly on the back of the asset swap program), non-mining investment looks to be bottoming at last and export volume growth is strong.

What about a house price crash?

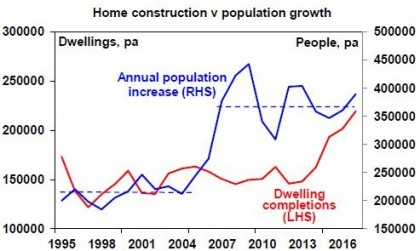

Yes, there is a risk of a house price collapse but it’s a lot more complicated than most people think as pointed out in my last house price note http://bit.ly/2y97kCE . Basically: we have not built enough housing to keep up with strong population growth since mid-last decade (see the next chart); the boom lately has been confined to Sydney and Melbourne (which were more harmed than helped by the mining/China-related boom); and the deterioration in lending standards has been modest with, for example, little in the way of the NINJA (no income, no jobs, no assets) loans that caused so much trouble in the US.

Source: ABS; AMP Capital

Sydney and Melbourne home prices are likely to fall by 5-10% (like in 2008 and 2011-12) but a crash is unlikely unless unemployment goes up a lot (unlikely), the RBA raises rates aggressively (again unlikely) or the current unit supply surge continues for several more years (again unlikely with approvals off their peak).

More than “dumb luck” in Australia’s 26-year expansion

While luck has played a role in Australia’s 26 years of economic expansion, it’s worth noting that the China-related boom only really ran for eight or nine years of it (from 2004-2012), and a significant contribution came from the economic reforms of the 1980s and 1990s that made the Australian economy more flexible in responding to shocks. Also, sensible economic policy meant that we managed the China boom well (by avoiding an overheating economy and running budget surpluses), which meant we were better placed to ride out the global shock from the GFC and the subsequent end to the commodity and mining investment booms.

26 years of economic expansion has left the Australian economy with lots to show for it: the economy is 129% bigger in real terms than it was when the 1990-91 recession ended, per capita GDP is up 61%, unemployment is less than half its early 1990s high and our dependence on foreign capital as measured by the current account deficit relative to GDP is about one third smaller than it was 26 years ago. Sure we can do better – underemployment, weak wages growth and poor housing affordability are serious problems and we seem to have given up on serious economic reform – but the economy is in better shape than some give it credit for.

Australia versus the world

Finally, I should note that while we are not in the crash camp for Australia, we remain of the view that it will be a while before interest rates can rise and that Australian economic and profit growth will be subpar compared to other countries for a while yet. As a result, we remain of the view that while Australian shares have more upside they are likely to remain relative underperformers versus global shares for some time yet and that the Australian dollar still has more downside. This is really just a continuation of the “mean reversion” of the huge outperformance in Australian shares versus global shares and in the Australian dollar seen last decade.

Important note: While every care has been taken in the preparation of this article, AMP Capital Investors Limited (ABN 59 001 777 591, AFSL 232497) and AMP Capital Funds Management Limited (ABN 15 159 557 721, AFSL 426455) makes no representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This article has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this article, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This article is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided.